Afterword—An FAQ of Sorts

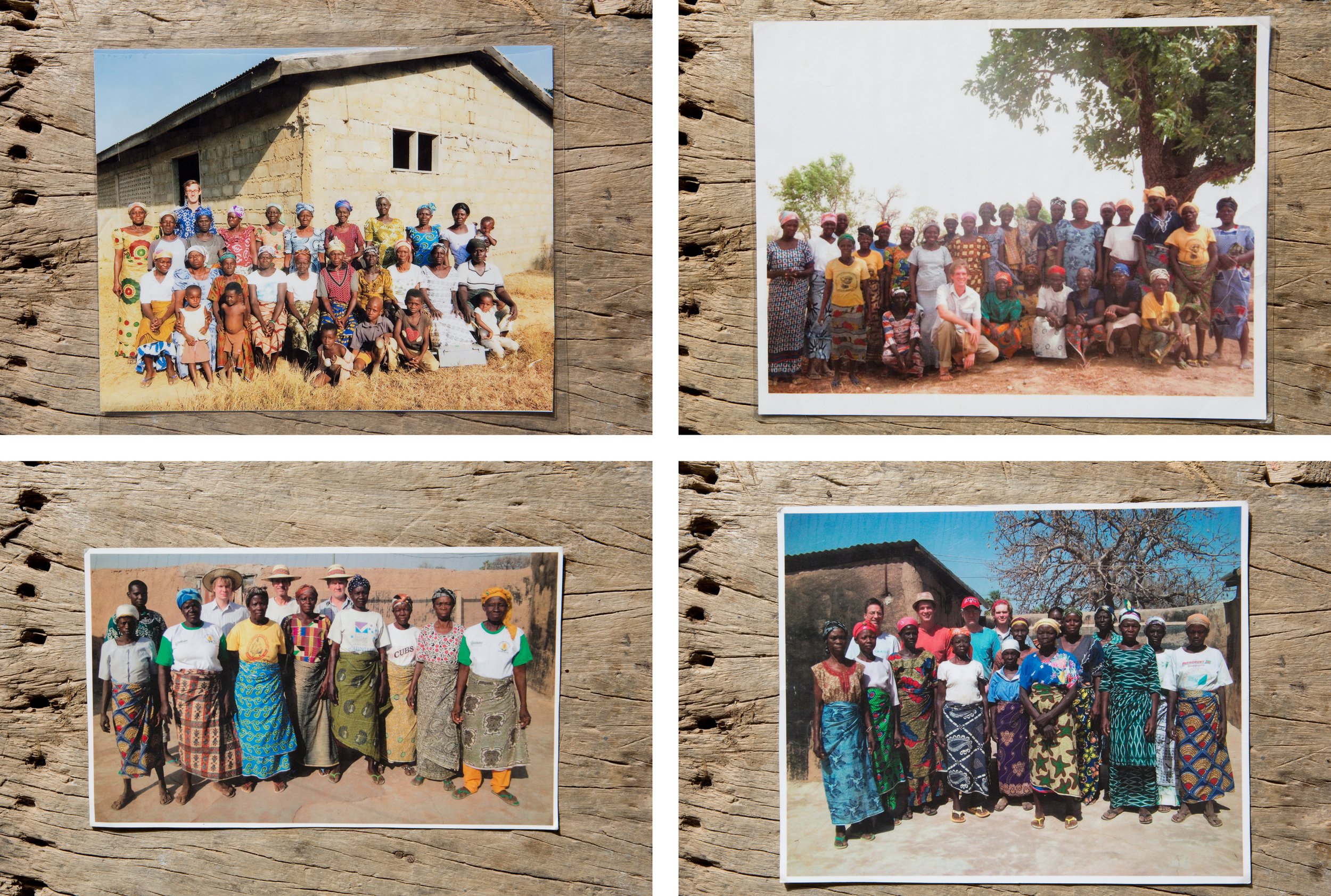

White supremacy is reliant on media stereotypes in order to maintain its dominance. Just as Black Americans have been historically (and contemporarily) portrayed as lazy, dangerous, or untrustworthy, white supremacy relies on stereotypes of Black Africans as needy. This project dovetails with my work on Everyday Africa; my photography is an exploration of the stereotypes the West has developed of other parts of the world in order to exert its imagined superiority, and of the results of those false imaginings.

When I share this photography with people, they often do not know what to think of it. It is a disruption to accepted narratives. It is also a real downer. In our collective imagination, Africa is there to be helped, and people need to feel that they can. People try to make sense of this project by asking what I feel are the wrong questions.

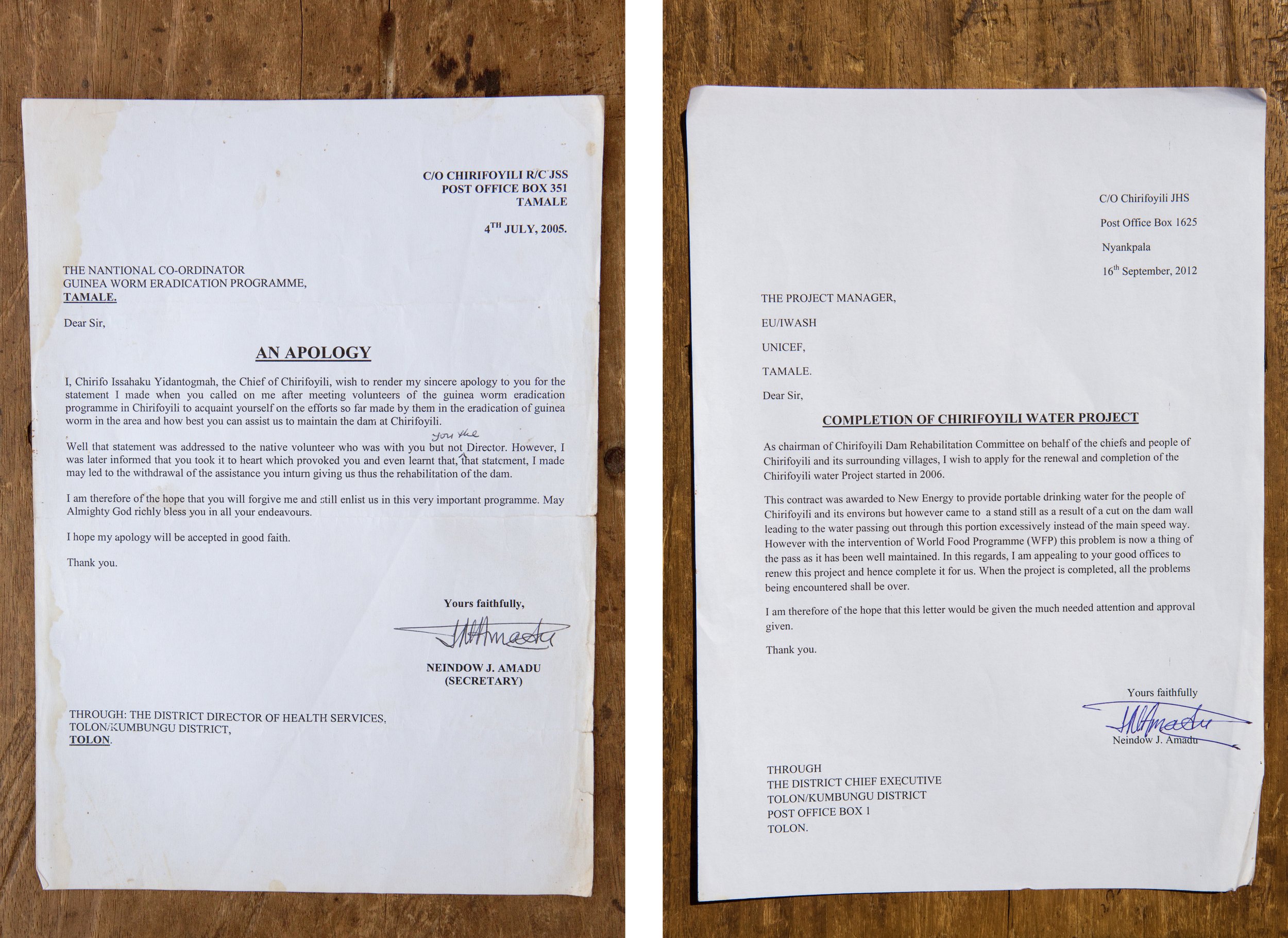

“How much of each dollar sent to Africa for foreign aid do you think actually gets used?”

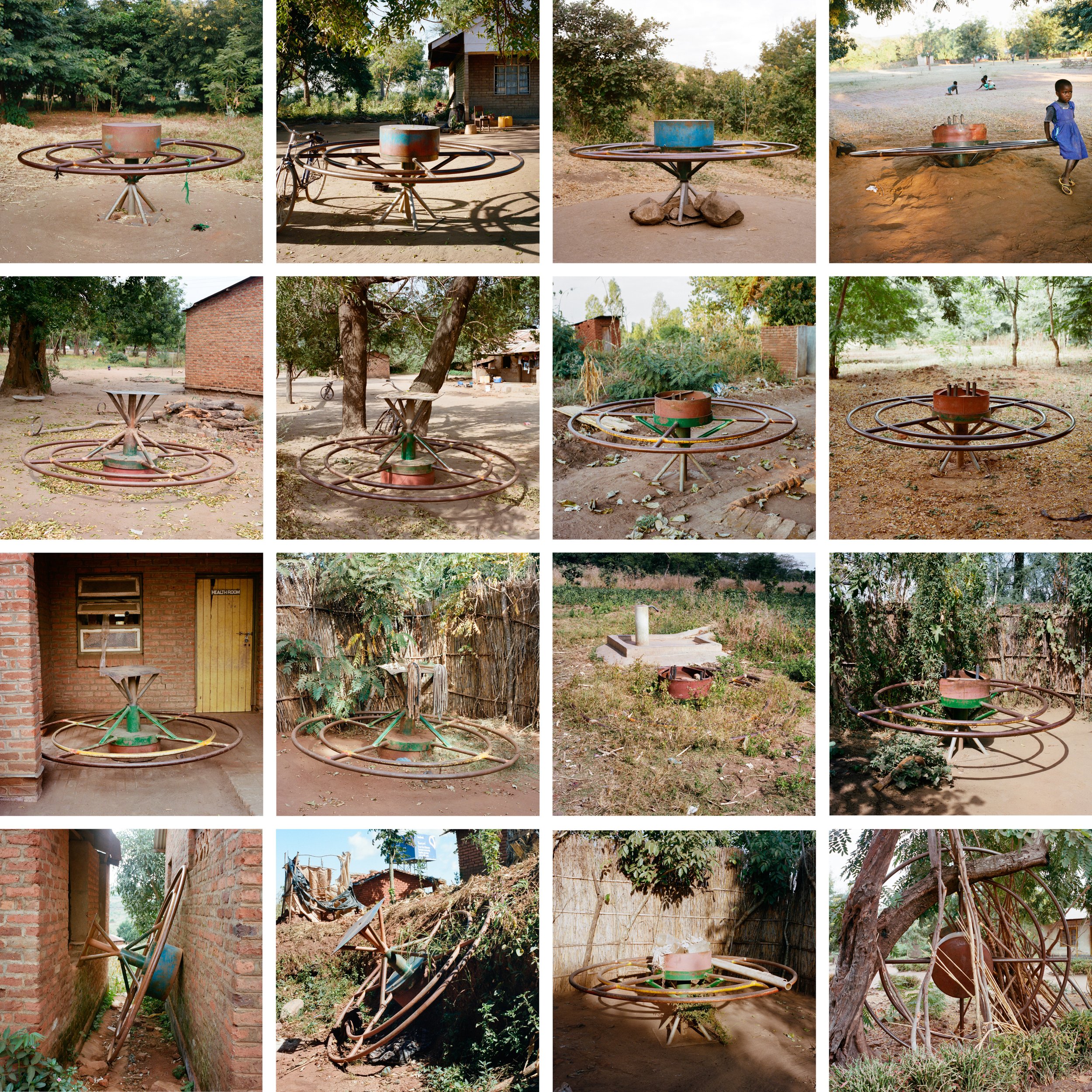

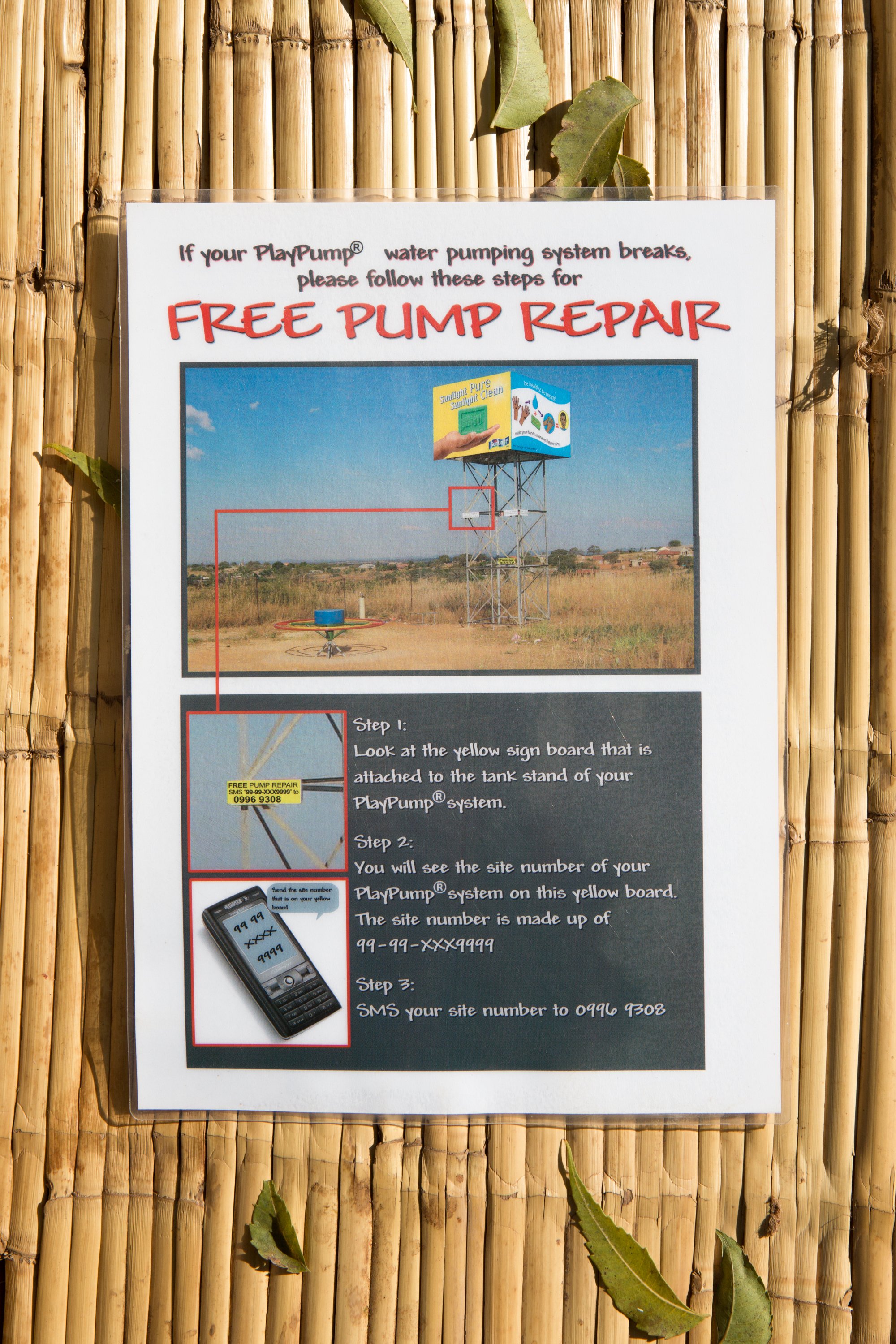

It is an impossible question. The typical metric here is how much of each dollar is used for programming versus overhead, a number that NGOs often use when appealing to the public for donations. But, how much of each dollar goes toward programming that fails after a year, or programming that no one wants or needs? If the money for, say, the PlayPumps I photographed in Malawi — which replaced functioning handpumps, and which broke down, and which no one local could fix and no one from the company came back to fix, and which never even pumped much water in the first place — if 100% of each dollar went to programming, and the programming was harmful, then what good was the dollar, or the percentage, or the question?

At one artist talk I was giving, I started explaining this to the man who asked this question, but my long answer was too much for him. He wouldn’t let me off the hook. He wanted it simple. “I’m just trying to ask,” he repeated, cutting me off, “how much of each dollar to Africa is helpful. Do you think it’s less than half? “ “Sure,” I stuttered.

We are societally dedicated to a simplistic, damaging narrative. Breaking from hegemony is difficult.

"Do you hate NGOs?"

I don’t want to disparage people’s good intentions. But I cannot accept the notion that good intentions should put anyone beyond criticism.

“Aren't there any successful projects? How do you do it right?”

There are many obvious failures in the stories I have reported, but there are also some successes within them, projects that served a community for a few years before ultimately breaking down. How do we judge success? Is it some equation of time and money and people served and for how long? There are many places where you can see stories of successful foreign aid. These stories are about the unsuccessful projects, and I am telling them so you know that they exist, and so you know that they are many.

“Do you also report on any solutions?”

It is worth stating that this is commonly from editors. I’ve found it difficult to get this work published. “It’s too negative,” they often tell me. These are the same magazines who regularly put photographs of war and suffering in their pages. When a journalist reports on war, we do not say, “yes, but you should tell us the solution in your story.” I understand what “too negative” means: it means it does not fit the narrative. It is not within the range of our palate of acceptability. Never-ending war, for example, is something we can stomach, something we have deemed societally acceptable to see in our news. The idea that our help may be unneeded, unwanted, or harmful in sub saharan Africa is not.

We cannot make people feel helpless.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Magnum Foundation, Brown Institute for Media Innovation, Code for Africa, Pulitzer Center, Devex, and Photo Festival en Baie de Saint-Brieuc for their support of this project. I am eternally grateful to them for their belief in this topic and this work.

Joe Wheeler worked with me over numerous years to conceptualize this project. He is the best co-conspirator anyone could ask for.

Anthony Langat, Nurdin Elmoge, Philip Muhatia, Austin Merrill, and Harriet Dedman contributed to the reporting of these stories.

Return to home page

![Professor J E Elliott, Miami University faculty, who has run the Ghana Design/Build program since 2005: “[The library] was built before my involvement with the program began in 2005 though, and I have very little detailed knowledge of it. Ou](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a9cc830f2e6b16b58c62ad6/1643244360876-T42X7BNDOEPVDKMIV3FS/ABRAFO_03_05.jpg)